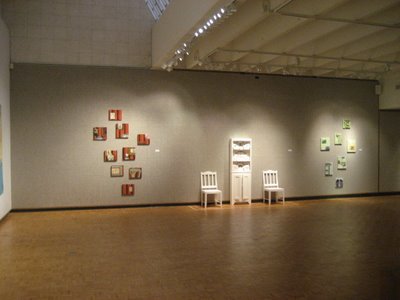

September 27-October 22, 2006

The Allen Priebe Gallery of The University of Wisconsin in Oshkosh

Co-curated with Yael Lipschutz

Susan Hamburger mines the traditionally female dominion of the home to unearth social and psychological dimensions of decorative objects. Her large and sensuously painted Truss canvases exhibit lavish, bound drapery that advertises seduction yet simmers with inner unease. The beauty and neuroticism of these tethered window treatments allude to the attraction of middle-class women to the endless project of beautifying their domestic surroundings. By contrast the Ongepatchket series depicts archetypes of interior design held up to the American woman as aesthetic models: ornate vases lie coquettishly aside lush velvet curtains in these nimbly painted canvases. That Ongepatchket is a Yiddish word meaning overly done or garish signals that these paintings are time capsules returning us to the home, and design aesthetic, of Hamburger’s immigrant grandmother. Though the modernist viewer may read these flamboyantly decorative paintings as a cultural critique, or even mocking appraisal, of such furniture, the artist’s investment of her customary care in the work’s execution conveys the other side of her intent: a sense of the furniture’s original intimacy and personal meaning. The relationship between decorative objects and socio-economic groups is also at play in the “cut-out” series, in which eighteenth-century porcelain dining sets serve as inspiration for Hamburger’s ersatz dishes. The originals were produced in factories for the British middle-class. Affordable, the plates became ubiquitous household items in the mid-1700s and only hundreds of years later evolved into the high-class collector’s items they are associated with today. Hamburger cunningly transforms and alters the meaning of this original cultural convention by a relatively slight shift in material and decorative emphasis. The faux porcelain plates, rendered in ink on foam board, come to us as simulacra, copies of a decorative tradition that was itself so removed from the original that Hamburger’s transformations register with more handmade vitality than their sources.

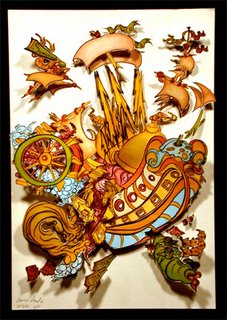

Conrad Vogel peoples his vibrant and deftly linear set-pieces with vanquishers and slaves, conquerors and bedraggled masses. His repertoire of gestural, figurative imagery is collected from historical periods, such as the American Civil War, and from his personal travels through the West Indies. Vogel references everything from contemporary cultural clichés and contradictions to the current war in Iraq. An awareness that two of Vogel’s primary inspirations are Candide and Uncle Tom’s Cabin helps one to recognize that his art is an unusually direct and principled cultural critique. But the theatrical nature of his work could not be clearer, as each rectangle is highlighted by a faux-baroque, high-arched frame, within which lurk his landscapes and heroes. Stylistically, the compositions draw upon traditions as diverse as the Japanese woodcut, the American comic book, and nineteenth-century peep-show theater sets. This last tradition, that of early optical entertainment and pre-cinema perspectival experiments, allows Vogel to breathe real life into his paintings, as he transforms thematic concerns into pop-up theatrical compositions. What results are highly beautiful, subtly sculptural reexaminations of the larger, original paintings. Though shrunk and compressed, the enigmatic three-dimensionality of these pieces allows the viewer to slip off the coils of culture and be overcome with actual wonder.

Text by Yael Lipschutz

Comments